Mar 7, 2005. - Newsweek

Playing the Class Card

BY ANDREW MURR

IN THE JURY BOX

There are no black jurors,

but the Jackson trial may hinge on something other than race. And

we don't mean the evidence.

We all know that the American justice system entitles the accused

to a jury of his peers. But, as Beverly Hills jury consultant Marshall

Hennington says, "What does a group of Michael Jackson's peers

look like?" Not much like the one seated last week in Santa

Maria, Calif.—and that may be good news or bad news. For

either side. The accuser is Hispanic, and a white district attorney

will prosecute Jackson before a jury with no blacks. But Hennington

(who happens to be black) says that's not the real point. "This

is not a case of race," he says, "as much as it is a

case involving child molestation—and the issue of class." We all know that the American justice system entitles the accused

to a jury of his peers. But, as Beverly Hills jury consultant Marshall

Hennington says, "What does a group of Michael Jackson's peers

look like?" Not much like the one seated last week in Santa

Maria, Calif.—and that may be good news or bad news. For

either side. The accuser is Hispanic, and a white district attorney

will prosecute Jackson before a jury with no blacks. But Hennington

(who happens to be black) says that's not the real point. "This

is not a case of race," he says, "as much as it is a

case involving child molestation—and the issue of class."

The jury that will decide whether Jackson molested a 13-year-old

boy after plying him with alcohol consists of seven Anglos, three

Latinos, one Asian and one person whose ethnicity was unclear as

of late last week. (Santa Barbara County is only 2 percent African-American.)

Perhaps more important, they're mostly middle-class folks, and

they may see Jackson as a remote, impossibly wealthy celebrity

who considers himself above the law. Jackson bought his way out

of a previous child-abuse allegation, paying

a multimillion-dollar settlement to a 13-year-old Los Angeles boy

in 1993. (Judge Rodney Melville has yet to decide whether evidence

from that civil suit will be admitted in this criminal case.)

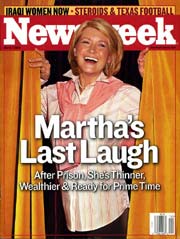

And, as happened in the Martha Stewart trial, jurors may be put

off by a parade of celebrity character witnesses. (This could also

backfire in another way: a 62-year-old juror, confronted with a

list of potential witnesses, thought Deepak Chopra was a rapper.)

On the other hand, jurors may see the accuser and his family as

lowlife con artists. Jackson's lawyers are calling the accuser's

36-year-old mother "a professional plaintiff," and they've

brought up a 1999 civil suit in which the family got a $150,000

settlement from JC Penney and Tower Records after mall security

guards allegedly roughed them up. (The guards claimed the family

shoplifted, though no one was prosecuted.) "What if the boy

lied in the past to help his mother obtain money through the legal

process?" one Jackson attorney

has asked in court. (In grand-jury testimony from the current case-leaked

to thesmokinggun.com— the mother denies ever coaching her

children to lie.) And certainly jurors will be asking themselves

what kind of a mother would let her kid have a sleep over at Michael

Jackson's house.

Even the family's heart-rending string of disasters could ultimately

work against them with jurors who hold such secure and respectable

jobs as engineer and government supervisor. "It's hard to

put yourself in the shoes of people who are having a medical crisis,

a financial crisis and an emotional crisis," says Loyola Law

School professor Laurie Levenson, a former federal prosecutor. "We

don't particularly identify with those people." During the

nasty 2001 divorce, the father admitted beating the mother and

children. That has no relevance to Jackson's guilt or innocence,

but it may not sit well with jurors. As USC law professor Jean

Rosenbluth puts it, "This is not the wholesome all-American

family."

But even if the defense can dehumanize Jackson's accusers, its

bigger challenge will be to humanize Jackson, with his surgically

sculpted mask of a face, his Neverland Ranch, his Peter Pan lifestyle—and

the tens of millions of dollars it takes to sustain it all. The

actual evidence could make these questions of class a moot point,

but don't bet on it.

Return to Top

Return to In the News

|

We all know that the American justice system entitles the accused

to a jury of his peers. But, as Beverly Hills jury consultant Marshall

Hennington says, "What does a group of Michael Jackson's peers

look like?" Not much like the one seated last week in Santa

Maria, Calif.—and that may be good news or bad news. For

either side. The accuser is Hispanic, and a white district attorney

will prosecute Jackson before a jury with no blacks. But Hennington

(who happens to be black) says that's not the real point. "This

is not a case of race," he says, "as much as it is a

case involving child molestation—and the issue of class."

We all know that the American justice system entitles the accused

to a jury of his peers. But, as Beverly Hills jury consultant Marshall

Hennington says, "What does a group of Michael Jackson's peers

look like?" Not much like the one seated last week in Santa

Maria, Calif.—and that may be good news or bad news. For

either side. The accuser is Hispanic, and a white district attorney

will prosecute Jackson before a jury with no blacks. But Hennington

(who happens to be black) says that's not the real point. "This

is not a case of race," he says, "as much as it is a

case involving child molestation—and the issue of class."